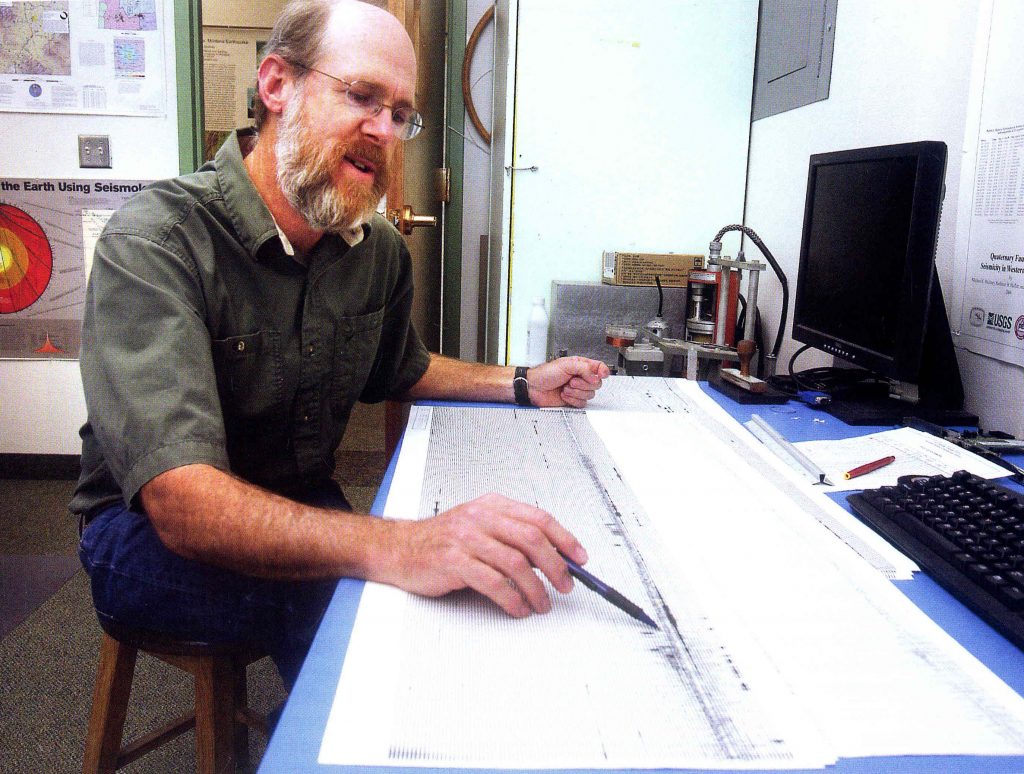

17 November 2017–A magnitude 5.8 earthquake in western Montana and a swarm of more than 400 small earthquakes around Yellowstone National Park kept Mike Stickney busy this summer. As the director of the Earthquake Studies Office at the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology, Stickney is the one-person seismology shop that the state relies upon for everything from equipment repair to data analysis to communicating with the public.

“Some individuals think that I sit here and watch the needle on the seismograph all day, waiting for something to happen,” Stickney jokes. “I assure them, no, it will record the data whether I’m watching it or not, and there’s lots of other things that I should be doing instead of watching it.”

Stickney is a Montana native, raised in Missoula, “and I was sure I was going to be a paleontologist when I started school,” he says. “But I lucked into a job at the earthquake lab at the University of Montana, worked there for a summer and got interested.”

After receiving his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at the university in 1980, Stickney was hired by the Montana Bureau to map faults in the Helena Valley. When funding was cut for three permanent seismograph stations in the state, he worked with the Bureau’s director to keep the state’s oldest continuously running seismic station operational at Montana Tech in Butte.

Stickney now devotes most of his time to operating the Montana regional seismic network, which covers everything from installing and maintaining equipment in the field to troubleshooting the transmission of data from 40 stations around the state and analyzing the data. The regional network had received some federal funding through the Advanced National Seismic System (ANSS) that paid for an analyst to work with Stickney, but when the funding was cut in 2014, we “reverted back to a single-person operation,” he says. He works with the University of Utah Seismograph Stations, which hosts the advanced software system that analyzes and archives earthquake data from Montana, “and that has been a tremendous benefit.”

He is often on the road: the state’s northernmost seismic station is about 300 miles and the southernmost station is about 200 miles away from Stickney’s lab in Butte. Over the years, he has learned how to troubleshoot the problems that crop up at these sites, from icing on antennae to removing tree branches that shade the solar panels that power the stations. The summer’s devastating fire season has also affected some stations, which Stickney must visit to repair before winter sets in.

“I’ve got replacement parts for everything that I can imagine has gone wrong, and hopefully I can put it back together and get the signal going again,” he says. “It’s been the school of hard knocks. I didn’t receive any training for being a seismograph technician. But we are actually fortunate that most of our sites will run well for multiple months without site visits.”

One of the big challenges for Stickney is the aging technology of the Montana network, much of which relies on data transmission (telemetry) through FM radio receivers instead of digital devices. “These low-power radios won’t shoot over mountaintops, so almost without exception our stations are up high on mountaintops or ridges, so we can have a line of sight between transmitter and receiver,” he explains.

Stickney is always on the lookout for opportunities and funding to upgrade the stations. A unique opportunity came two years ago, when the Montana Bureau was able to take over ownership of a seismic vault built by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers near Libby Dam in northwestern Montana. “They were getting ready to demolish it, and that was a part of the state where we really didn’t have monitoring,” Stickney says. “It took years of paperwork, but we established a broadband station with satellite telemetry.”

“We still have a foot in each world,” he notes. “We can’t afford to upgrade those old analog sites to modern instruments, so if we want the monitoring to continue, we have to keep the old stuff running. Anything that we add these days, we try to invest in digital seismology so that we have the quality of data that’s necessary for many of the modern analyses.”

Stickney continues to map faults in Montana, recently describing a fault on the front of the Bitterroot Range that cuts across relatively young geological deposits, between 12,000 and 15,000 years old, that has moved repeatedly through time. The data will help seismologists better assess the earthquake risk “in a part of the state where I can literally count the number of earthquakes that have occurred there, since we started monitoring, on the fingers of my hand,” Stickney says.

This summer’s earthquake activity has reminded many in his state that Montana is earthquake country, he notes.

“The state has a very active earthquake history, but our last devastating earthquake was 58 years ago,” he says. “So we have a whole generation of Montanans who have grown up or moved here who are not necessarily aware of potential hazards.”