| Publications: SRL: Historical Seismologist |

Historical Seismologist

May/June 2008

Tom La Touche and the Great Assam Earthquake of 12 June 1897: Letters from the Epicenter

Roger Bilham

University of Colorado at Boulder

Electronic Supplement: Transcriptions of Tom La Touche’s letters 1882–1910; a brief biography of La Touche illustrated with contemporary photographs.

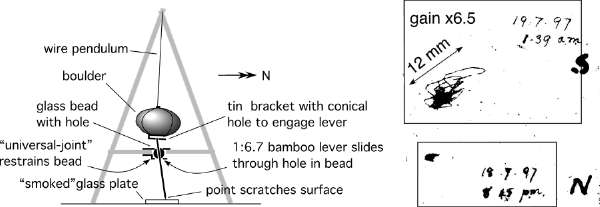

Richard Dixon Oldham’s classic memoir on the great Mw = 8.1 Assam earthquake of 1897 is seminal for its seismological observations, insights, and conclusions (Oldham 1899). Teleseismic arrivals of waves from Shillong led Oldham (1858–1936) to distinguish the three types of seismic waves and eventually to recognize from them the distinctive presence of the Earth’s core. Oldham, however, did not feel the earthquake. He had left the Calcutta office of the Geological Survey of India (GSI) in the care of his colleague Thomas Henry Digges La Touche (1856–1938) two weeks previously (see figure 1). Now recently discovered letters written by La Touche from Calcutta and the epicentral region to his wife, Nancy, provide a firsthand, day-by-day account of the post-earthquake investigation and include a seismogram from an instrument that he constructed in the field at a cost of “less than sixpence” from pieces of tin, a suspended boulder, a glass bead, and a bamboo needle that scratched a glass plate (LaTouche papers, 1880–1913).

In his memoir Oldham notes that he focused his team of geologists on the physics of the earthquake. Their reports were submitted “under specific instructions to report only on the facts observed, and to refrain from any expressions of opinion as to the conclusions to be drawn, as this could only be profitably done after a review of the whole of the facts, of which only part could become known to each individually.” (Oldham 1899, p.257). He deduced from their observations that local accelerations in the earthquake had exceeded 1 g, that velocities had exceeded 3 m/s, that electrical currents in the ground had accompanied aftershocks, that postseismic crustal deformation continued to deform the plateau in the year following the earthquake, and that many of the largest aftershocks lay 15 km beneath the plateau. Because he dismissed as frivolous most discussion of the societal response to the earthquake, anecdotal accounts of its effects are rare in his memoir.

▲ Figure 1. A young La Touche, probably taken when he joined the GSI in 1882 (courtesy of the Director General, GSI, Calcutta). La Touche was born two years before Oldham and died two years after him. [Click images to view larger versions.]

More than a century after Oldham published his account, La Touche’s recently discovered letters to his wife archived in the British Library, London, and transcribed here, reveal that Oldham, then acting director of the GSI, was hundreds of kilometers from Shillong at the time of the earthquake and quite unaware of its magnitude or the extent of its devastation. It took telegrams and letters to draw him back to headquarters in Calcutta, where his colleagues were busy documenting urban damage. Once aware of the seriousness of the quake he dispersed all available geologists (like a bombshell) to the damaged regions in northeast India. They returned with quantitative estimates of shaking, which, together with Oldham’s own traverse of the region in the winter months, formed a 62-page observational appendix to Oldham’s memoir. The first and largest of the field observation reports was contributed by La Touche. In this article, and more fully in an electronic supplement to this article illustrated with contemporary photographs, La Touche describes his experiences during the postseismic investigation.

La Touche wrote daily to his wife, Nancy (Anna La Touche, née Handy), whenever they were separated by his geological responsibilities. Because this occurred 8 to 11 months of each year, his letters provide a unique insight into the day-to-day operation of the GSI from about 1890 to 1910. His neatly folded four-sided letters to Nancy take the form of a starting page of nostalgic remarks about his love for his wife, often with a response to the content of her previous daily letter to him. The following is a poignant example from 25 June 1897: “I’m afraid you will find this letter very uninteresting. No I don’t mean that, for I know you to be interested in what I am interested in, but my head is full of earthquakes, and my heart is full of love for you. My dearest love to you sweet, Your own husband, Tom.” His letters invariably conclude with a page of hugs and kisses for his children. The central two pages describe what he did that day, and samples from these are extracted in diary form below. His communications with Nancy included letters sent to him from Oldham and others, some of which have been preserved in the archive.

In the late spring of 1897, Oldham was planning to spend three weeks in Nainital inspecting new provisions for hillslope drainage in which he had taken a personal interest ever since describing a catastrophic slide there shortly after his arrival in India in 1879 (Oldham 1880). His departure on 29 May had been delayed by a day due to an accident in which he was thrown from his horse and cart, which had left him badly shaken. La Touche, who was asked to oversee the Calcutta office in Oldham’s absence, wrote to his wife that he would have little to do, not realizing that within two weeks the largest earthquake in the history of the British Raj would shake Calcutta, its administrative center. The Shillong Mw = 8.1 earthquake occurred at 17:11 local time, Saturday, 12 June 1897, and within a minute and for the next several minutes surface waves from Shillong rocked Calcutta, causing widespread but minor damage in the city (seismic shaking intensity V). Nainital lay in the Intensity III zone, and Oldham may not have felt the earthquake.

A series of excerpts from La Touche’s letters to Nancy details the days following the earthquake:

Calcutta, 13 June 1897

It was really a most alarming experience. I have felt a good many earthquakes out here, but nothing so like as bad as this one. I was lying on the sofa of my room here at the hotel, which is on the upper story, having my tea when it began, just at 5 o’clock. At first it was very gentle, just a slight rattling of doors etc, and I thought it would be soon over, but it got worse and worse until the floor of the room was heaving like the deck of a ship at sea. I thought it was time to leave then and started for the door, but remembered that I had no coat on and went back for it. I confess I was most frightened in those two or three seconds I was getting my coat than I have ever been before. When I got out on the landing I found every one getting down the stairs as fast as they could, some of the men in pyjamas. Down below it did not feel as bad, but we all got out on the maidan [the Calcutta parade ground] as soon as possible, where we could see the houses and even the trees rocking to and fro. It was a very long earthquake, lasting between 4 and 5 minutes.

I have got as many of the survey men as I could get hold of at short notice to go around and take photos, & Mr. Hayden [Henry Hayden, who became director of the GSI in 1910] and I have been hard at work all the morning. We went to the old cemetery where there are a lot of tall pillars and obelisks and got a couple of very interesting overthrows which will help us to calculate the direction and force of the earthquake.

Calcutta, 14 June 1897

The damage done is enormous. A great many houses ought to be rebuilt entirely but the native owners will probably only patch them up till the next big earthquake comes and then they will collapse entirely.

Calcutta, 15 June 1897

We are still engaged investigating the earthquake trying to get as much information as possible before the rains come for a great many of the damaged houses will be falling if heavy rains come and it will be impossible to say if the damage was caused by the earthquake or by the rain.

Calcutta, 17 June 1897

The excitement about the earthquake is calming down a bit but it is still the main topic of conversation. A good many people are nervous about a prophesy that there is to be another soon, but no one heard of it till this one had come and one, of course, cannot foretell such things. We had a few very slight shakes since but that was to be expected. After the 1885 earthquake [in Kashmir] there were smaller shocks till the end of September.

Calcutta, 18 June 1897

The news from Shillong is very bad. Mr. Oldham has woke up at last to the magnitude of the affair and is coming down at once. He felt hardly anything at Naini Tal.

On June 17, Oldham had written to La Touche:

Naini Tal, 17 June 1897

I have just got your letter of 15th. You seem to have done everything that could have been done except send me full news by wire and I am much obliged to you for what you have done. I have just wired that Hayden should go to Darjiling as soon as possible. The direction you give at Calcutta places the seismic vertical somewhere about the Garo Hills or further north in the Himalayas, probably the former, and the Darjiling observation will be valuable. Had he known of the severity of the earthquak e Oldham would most certainly have left Nainital earlier. Obliquely describing himself in the introduction to his 1899 memoir, he states that at the time of the earthquake there was only one person in the GSI “who had paid any special attention to the subject of earthquakes, or had any knowledge of the nature of the observations required, beyond such as might be obtained from the ordinary curriculum of a geological student.” (Oldham, 1899, p.1). He based this claim on his completion of his father’s articles on the 1869 Cachar earthquake and catalog of historical Indian earthquakes (Oldham 1882 a, b).

La Touche continued his observations in letters to Nancy the week after the earthquake.

Calcutta, 19 June 1897

Mr. Hayden is getting ready to go up to Darjiling to make observations. A great deal of the line is broken down and he will have to do that part of the journey by trolley, so he will not get up there till Tuesday. I think the report on this earthquake will be the best illustrated one in existence. We must have somewhere about 50 negatives to choose from.

Calcutta, 21 June 1897

Mr. Oldham’s arrival has been like that of a bombshell. Mr. Vredenberg is sent off up to the East Indian Railway, and Grimes to Sylhet and Cachar, Hayden has already gone to Darjiling. I have been very busy all day getting things ready.

Calcutta, 22 June 1897

I have been very busy all day as you may suppose. In the first place I got up at 6 and spent the morning before breakfast writing an account of the earthquake for Nature to go home by today’s mail. I showed it to Mr. Oldham, who approved of it.

The title of La Touche’s (1897) Nature article was “The Calcutta Earthquake,” since his experience of the event up to 22 June was biased, as was Oldham’s, by the damage he and his colleagues had documented in the city. Reports from the epicenter 150 km to the north indicated substantial damage but were secondhand, and telegraph lines were down. On 24 June 1897 in an editorial piece, Nature summarized incoming information including the exaggerated estimate by the Chief Commissioner of Assam of 4,000–6,000 fatalities on the Shillong plateau (the final death toll in the whole of northeast India was fewer than 2,000). However, had the earthquake occurred during torrential rain a few hours earlier, or after dark a few hours later, the death toll would have been an order of magnitude larger. La Touche’s (1897) Nature account was published 22 July 1897 and emphasizes shoddy construction as the chief reason for building collapse in Calcutta.

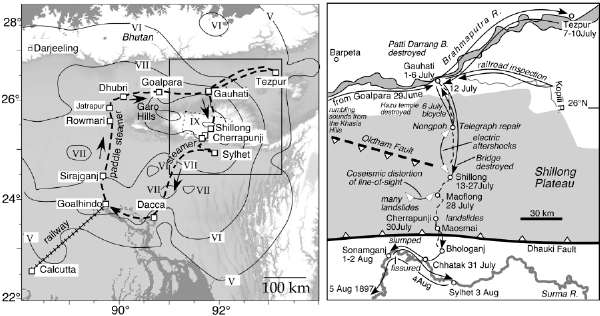

Oldham dispersed his team with instructions that they measure the fall of objects. He assumed as did others at the time that the direction of collapse of tombstones, gate posts, and obelisks would radiate from the epicenter, then termed the seismic vertical. La Touche first made his way by rail and paddle steamer (figure 2) via a number of increasingly damaged Brahmaputra river towns (see the electronic supplement to this article) to the region of extensive damage at Dhubri (Intensity VII). Thirty-three years later Dhubri, near the northwest corner of the Shillong plateau, was the epicenter of an M 7 earthquake almost directly beneath the town (Gee 1934).

La Touche’s letters to Nancy describe what he saw on his travels.

Dhubri, 25 June 1897

[The district commissioner] had a very narrow escape from his own bungalow, which is the worst I have seen yet. Absolutely nothing but a shapeless heap of bricks. He was reading at the time when the earthquake came and had only just enough time to run out when the whole thing came down. He is living now, camp fashion, in a bungalow with nothing but mat walls and a timber roof belonging to the local board. Nearly every house in the place is a wreck. The doctor, an old friend of mine, is living in his stable, with a few sticks of furniture he has saved… There are two or three interesting results of the earthquake here which I shall have to investigate critically tomorrow and make plans & measurements of them [reproduced in Oldham 1899, 260]. The bungalows don’t help one much they are so utterly smashed up. They still have slight shocks here—there was one 5 minutes ago which shook the house quite distinctly—but the people are getting quite used to them and only say—Oh here’s another (!) when they come. It is most extraordinary to see the way the ground has cracked and opened about here. All along the river banks and on the roads in every direction there are huge fissures and generally mud and water has been thrown out from them.

Dhubri 26 June 1897

I did a great deal of work here this morning and made some measurements but most things are so entirely broken up that we cannot make much out of them. I shall most likely go up the river tomorrow to the next station, Goalpara. Every house they say is wrecked there and I must take a tent with me.

Goalpara, 28 June 1897

I am now really seeing here what the effects of the earthquake have been, it is even worse than Dhubri. I came ashore early this morning when the steamer left and walked through the bazaar. Nearly all the houses in it are half buried, up to the eaves in sand and mud which was thrown out from cracks in the ground, and it is a wonder that most of the people were not buried. Only two of the European houses are standing at all: the steamer’s agent, who is putting me up, and the mission bungalow, which was built entirely of timber. The walls of this are of cutcha and plaster and are gaping everywhere, but the roof is sound. I have counted 15 distinct shocks since 3 o’clock this morning and they seem to be getting more frequent as the evening comes on, but they are all very mild and just shake the house. One generally knows they are coming from the rumbling noise one hears just before them.

Goalpara lies on the northwest promontory of rocks of the Shillong plateau and was damaged by a surge from the Brahmaputra river. It is judged to have experienced intensity VIII shaking, which destroyed the bazaar and well-built houses. Despite liquefaction near the river, a few brick houses were left standing (Ambraseys and Bilham 2003). An analysis of geodetic data obtained in 1869, 1897, and 1939 suggests that subsurface reverse slip (≈ 15 m) in the earthquake occurred between ≈ 35 km and 9 km depth, on a 110-km-long south-dipping fault with a surface projection approximately in line with the city but terminating to its ESE (Bilham and England 2001). Oldham (1899) recorded more than 10 m of surface slip on the Chedrang normal fault above the northwest end of this main rupture, a region of local ponding and abandoned river channels.

Leaving Goalpara, La Touche steamed 100 km eastward along the swollen Brahmaputra with the northern edge of the Shillong plateau to the south. In his 3 July letter Oldham suggested that the river at his destination, Gauhati, was higher than usual as a result of downstream bank collapse. The geodetic solution indicates that the bed of the Brahmaputra and the valley to the south were tilted down to the south in the earthquake with a maximum of ≈ 25 cm of subsidence along much of the Brahmaputra. This would have further deepened the river between Goalpara and Gauhati.

▲ Figure 2. (left) La Touche’s epicentral route superimposed on an isoseismal map of the 1897 earthquake (Ambraseys and Bilham 2003). His “earthquaking” investigations from Gaolhindo to Sylhet traversed MSK Intensity VI–IX and were comparable to inspecting damage along the entire length of the 1906 San Francisco rupture (477 km). He returned from Sylhet along a path that had been inspected in detail by one of his colleagues (Grimes). The inferred 1897 rupture is shown by the dashed rectangle beneath Shillong, and right, as a line representing the upper edge of the inferred causal “Oldham fault” (Bilham and England 2001). The doubleheaded arrows (right) indicate the locations where La Touche reported coseismic surface deformation (west of Maoflong) and electrotelluric potentials induced by aftershocks (between Shillong and Nongpo).

Arriving at Gauhati La Touche encountered Intensity VII damage, as noted in the following excerpt from a letter to Nancy.

Gauhauti, 1–3 July 1897

I went round this morning and saw a lot of the damage and found some interesting falls of gate posts etc. The District Commisioner’s head clerk has just been here showing me the reports received from outlying places in the district . . . a temple not far from here, at least 300 years old, is destroyed. I have asked Mr. Oldham if I may not go back to Calcutta through Shillong and Cherrapunji. I believe the road is open nearly the whole way now and I should like very much to see what damage has really been done.

Oldham welcomed La Touche’s suggestion to return south from Gauhati, crossing the Shillong plateau and through the hill stations of Shillong and Cherrapunji (figure 2), which they knew had been severely damaged. Neither knew that this would take La Touche across the inferred surface projection of the subsurface 1897 rupture zone.

Oldham wrote the following to La Touche:

Calcutta, 3 July 1897

My Dear La Touche, I just got your telegram and am glad to hear that you were willing to go to Shillong and Cherrapunji. I got a letter from Watts, the engineer, enclosing a record of the gauge readings of the Brahmaputra at Gauhati, which show a sudden rise of 8 feet immediately after the earthquake and gradual fall afterwards. This is partially due to falling-in of the banks. I would be glad if you would enquire about it. When in Shillong get a set of photos. There are two babus who have been photographing. Order a complete set, or leave out such as you think has nothing to do with the earthquake, to be sent to me. Very likely I will order more copies of some but that can be done afterwards. Also try to get photos of the monuments and buildings as they were before the earthquake. I have some other evidence, in letters, of Barisal guns occurring with the earthquake shocks but they also are said to occur without, and to have been frequent before the big earthquake. The evidence will want careful sifting, however.

La Touche was familiar with Barisal guns, audible micro-earthquakes that were reported near the town of Barisal, Bengal, because he had published an article, and given a talk in England, about them (La Touche, 1889; 1890).

He wrote the following to Nancy:

Gauhati, 4 July 1897

I have pretty much finished the earthquake work here and this morning took it easy, but tomorrow I want to ride some distance up the Shillong road and to see what the bridges are like.

Gauhati, 6 July 1897

I had a 60 mile ride yesterday up into the hills along the Shillong Road. I went as far as Mungpo [Nongpo], 30 miles from here, and back again in the evening. [See figure 2.]

Tezpur, 8 July 1897

The east end of the church has been knocked out and some buildings are badly cracked, but none have come down entirely.

Tezpur, 9 July 1897

Col. Gray lent me a letter to read written by a man whom the C.C. [Chief Commissioner] sent out to Cherra soon after the earthquake to look after the people. It gives an extraordinary account of the ruin along the road. For miles and miles the whole of the road is utterly gone and all the bridges and rest houses are smashed. The unfortunate clerks (European) at Shillong who had been investing their savings in houses have lost everything.

Gauhati, 12 July 1897

I have been out all day on the railway which is really worth seeing. I went out 40 miles from here in a train starting at 7 this morning. Every here-and-there the embankment has sunk down and the rails are all twisted, but the engine somehow or other gets along. Of course we went very slowly, only 4 miles an hour or so over the bad places. It is very interesting to see how the bridges have been affected by the earthquake.

Oldham wrote the following to La Touche:

Calcutta, 12 July 1897

My Dear La Touche, I got your letters of 8th and 9th yesterday, and sent a telegram to you, directed to Shillong yesterday. Smith forgot a lot of things at Shillong, especially to take measures of the overturned monuments, I also want to know the dimensions of the seismometer cylinders. I fancy they are the same as those in the appendix to Mem. XIX, but there is no record of this. [See Oldham 1882a.] I was interested to hear of the twisted monuments. I hope you took the old and present bearings of all. I don’t know whether you know that with enough observations one can get a very good direction out of them? Yours sincerely, R. D. Oldham

A letter now in the collection of the Centre of South Asian Studies at the University of Cambridge provides an eyewitness account of the earthquake, mentioning many of the same people that La Touche encountered during his two-week survey in Shillong, 13–27 July 1897 (Sweet 1897).

▲ Figure 3. This collapsed bridge outside of Shillong was thrown from its abutments by the earthquake shortly after Mr. Monaghan and Mrs. Sweet had ridden over it on horseback.

May Sweet wrote to her sister Mrs. Godfrey:

Shillong, 28 June 1897

At 5.30 on Saturday last, the 12th June was as usual, and 30 seconds afterwards was completely in ruins. I was riding on the Gauhati Road with Mr. Monaghan, and suddenly we heard a queer rumbling sound and then trees swayed every way. Luckily by instinct we both turned sharply to the left and galloped up the hill as far as we could and find a place. We had crossed the bridge which would have gone down under us. [See figure 3.] I can’t possibly describe the sensation as it was so totally different from anything I had ever experienced. I did not know whether I was on my horse or not or on the land or in the air. I could do nothing as the ground was all in a whirl. I know I looked once at Mr. M. and he was as pale as death. We neither of us thought of an earthquake, we thought it was a landslip on the Gauhati Road. Of course, when we got up to the mission we saw something of the terrible ruin, the poor missionaries, they were all on the road with their houses flat on the ground and old Miss Jones in a dying state. We stopped to make her as comfortable as possible and then rode on towards the station (she died a day or two afterward). We could not go by the ordinary way until we got to the ground as it was all burst open and there were continued shocks the whole time. It was terrible riding home. Until we got to the bazaar I never realized what must have happened in the [hill] Station.

Today we’ve had very few shocks and hope they are nearly over—but they are always worse at night. A great many people are in the back sheds, and have two or three sharing a mattress. Another awful thing was that the water supply ran out and there was a fear of Cholera breaking out. Potatoes too were scarce as everything was buried but they are being dug up by degree and they say that in a few weeks the road will be made for fresh ones to be brought up—of course everything was an awful price. The ponies are fed on 1 seer pack or turned out to grass. Pearl behaved beautifully all the time. The only way they kept their feet was that they galloped. I really am most comfortable now for have got bashas built and I suppose we’ll have to live in them for months. Every day we dig a few more things out of the bungalow also; it is very slow work. Still I have a good many things that are presentable after being cleaned.

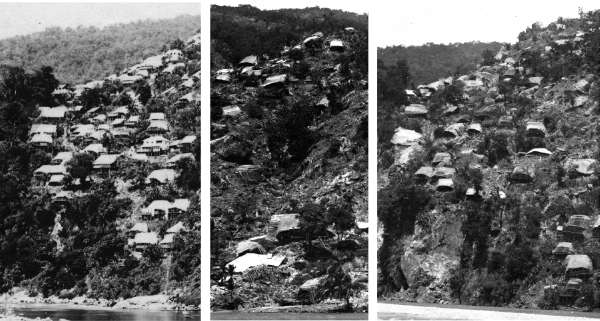

La Touche arrived in Shillong late on 12 July, two weeks after Mrs. Sweet’s letter had been written. He passed the damaged bridge shown in figure 3 and the land-slide damaged village shown in figure 4 and was now surveying a scene that he had first viewed 14 years earlier (La Touche, 1883). He stayed in a tent roughly 1 km west of the Public Works Department (PWD) where he eventually devised and operated a seismoscope (see the Shillong map in the electronic supplement to this article). He purchased a set of before-and-after photographs of damage, and some of these appear in Oldham’s report along with photographs taken by La Touche himself. I have illustrated this article, and its electronic supplement, with a series of images from a contemporary album purchased from a U.K. bookshop (figures 3–8) that were taken by the same Shillong photographers.

La Touche’s letters to his wife continued, including the following excerpts:

Shillong, 13 July 1897

It is only when one gets among what used to be the houses that one realizes what has happened. The walls and chimneys of all the houses are simply shapeless heaps of stone. I am staying with Col. Maxwell, living in a small tent while he is in one of his servant’s houses. His bungalow has not fallen as it was built of lathe and plaster, but the chimney came down and wrecked the whole of the inside. The whole house is leaning to one side like a house in a nightmare.

Shillong, 14 July 1897

This side of Mungpo [Nongpo] there had been a great many landslips especially in the last 8 miles but they had all been cleared sufficiently to allow carts to pass so we got here about 5:30 pm. The last big bridge on the road about 3 miles from here is entirely gone ~ We went to see the Chief Commissioner, Mr. Cotton, and I had a long talk with him and expounded my views on the shock. He had been reading the reports on the Cachar earthquake of ‘69 [Oldham 1882a] and was full of seismic verticals and other technical terms. There are a good many interesting things to be seen in the cemetery where several tombstones, great heavy blocks of marble or granite have been pushed sideways or twisted round, and I have seen several gate pillars which have been thrown over. I expect our report on this earthquake will be the biggest and best illustrated on record. It is most extraordinary that so few people were killed here, for by all accounts the houses came down with a roar almost at the beginning of the shock. Of course there were very many narrow escapes. Colonel Maxwell was hit by a stone from a falling chimney, and he told me of four children who were having a tea party who were saved by their nurses picking them up and rushing out, just as the chimney fell smash on the table they were sitting at.

▲ Figure 4. Hillside collapse of a local village near Shillong: before (left), after (center), and in the weeks of post-seismic reconstruction (right). A masonry structure in the center has entirely collapsed. In many cases walls have pancaked in situ beneath their roofs; in other locations houses have been swept downhill by local landslides.

Shillong, 15 July 1897

I spent all the morning and part of this afternoon measuring the monuments in the cemetery; a great many of them have been thrown down or shifted. There’s a little shock just gone by—shook the table distinctly. I must really see if I cannot rig up some kind of seismometer for observing these little shocks. I am sure one could learn a lot about the big one from them. This morning we had two very respectable shocks (there—another lasting quite a long time) but people take very little notice of them now, only everyone objects to sleep under anything like a roof. But I think that everything in Shillong that can come down, has already fallen.

▲ Figure 6. The bridge across the almost empty Ward Lake in Shillong after the 1897 earthquake. The dam holding the waters of the artificial lake burst in the earthquake, killing Mr. J. W. Rosenrode, a retired geodetic surveyor, and a child. The 2003 image (right) shows the bridge reconstructed with lateral stays.

▲ Figure 8. All Saints’ Church before and after the earthquake. The image on the left is identical to that shown by Oldham (1899), but the image on the right was taken a few feet away and permits a stereographic view of the damage.

Shillong, 16 July 1897

I have been pretty busy today measuring gateposts and such all the morning and rigging up a seismometer this afternoon. It is a rough sort of a thing made up of a lump of stone hung on a wire for a pendulum, a few pieces of tin cut out of a biscuit box, a slip of bamboo and a glass bead from a necklace. It is not put up yet as I am getting a small hut built to put it in, but I hope it will work.

Shillong, 18 July 1897

I have my seismometer put up and am now sitting waiting for an earthquake to see if it will work properly . . . here’s a little shock now but I’m afraid it’s too slight to affect my pendulum. Yes, it did move, but too slightly to show anything definite.

Shillong, 19 July 1897

This morning I had a long tramp down to the Bishop’s Falls to photograph the landslips there [see Oldham 1899, pl. 3] and did not get back to breakfast till nearly 1 o’c. Then all the afternoon I was making prints of the earthquake diagrams I got on with my seismograph which is a great success. This morning we had a real good shock at 20 minutes to 2 which woke me up, and I at once got up and went to see if the machine had acted and found a nice little trace of the shock. There is a needle in it that makes a trace on a piece of smoked glass. Then again at 10-minutes-to we had another pretty severe shock, which also registered itself, and during the day there have been several of them.

Shillong, 20 July 1897

There was another good shock this morning which my seismograph duly registered, and then there were one or two smaller ones at night. I send you one of my earthquake diagrams [figure 9]. It shows how the ground moves but is magnified about 6½ times. So you see these shocks are very small affairs really.

Shillong 22 July 1897

We have only had slight shocks today. Neither of them any good from my point of view as they have hardly any effect on the seismograph, but perhaps we shall get a good one tonight. There—a slight shock at 6:26 pm.

Shillong, 23 July 1897

I have had a pretty tiring day. I have finished the new seismograph, but the hut for it is not entirely ready yet.

Shillong, 24 July 1897

I have been working all the afternoon at my earthquake report, drawing out the plans of the gateposts all to scale.

Shillong, 25 July 1897

I have just been down to my seismograph to see if it registered any quakes during the night, but there was only a very small one. I think it came about 2 o’clock. I have been very busy all day at these plans and have a good number of them finished so I am feeling good! They take rather a long time to do but it is not difficult work. I only hope that Mr. O will appreciate it. There was a fairly strong earthquake shock about an hour ago (6 o’clock) but I don’t think it could have had any effect on my seismograph. However, I must go and see. No, it has only moved the slightest little bit.

Shillong, 26 July 1897

I have just come back from the PWD office where I have been to see how my seismograph shed is getting on. They say it will be finished today so I hope to get away tomorrow.

Maoflong, 27 July 1897

After breakfast I went to the PWD office and set up the seismograph. The hut was barely finished and indeed, while I was setting it up, the Chinaman who built it was putting on the door. As now it was up and I had explained the working of it to the people who will have charge of it, I started for Maoflong. The dak bungalow is wrecked, of course, only the roof standing, but a grass hut has been built.

▲ Figure 9. La Touche omitted a schematic of his seismoscope, and his wife in a responding letter complained about its omission. The figure left shows how it may have been assembled from La Touche’s parts list, guided by Ewing pendulum geometries summarized by Milne (1898, 320). The pendulum is depicted experiencing an acceleration to the north: friction in its several pivots and sliding parts provided damping. (Right) La Touche sent a postage-stamp-sized print of two Shillong aftershocks with his letter to Nancy on 20 July indicating a scale amplification of about 6.5, hence the maximum ground displacement was about 2 mm. Two aftershock traces are recorded on the same glass plate, which he offset between events. Three days later in a letter to his father, La Touche included a third seismogram from a 06:50 aftershock on 19 July (Rev. J. D. La Touche 1897). In this letter La Touche mentions the resemblance of his seismoscope to one designed by Ewing and indicates an amplification factor of 6.7.

Cherrapunji, 30 July 1897

Mr. Arbuthnot, the Deputy Commissioner, is going about to the different villages to find out how many people have been killed. The first accounts were very much exaggerated, and it is doubtful whether more than 500 or 600 were killed in the whole of the hills. Most of them were killed out of doors by landslips. In Cherra the people who stayed in their houses were all right, as the walls are very low, and the roof held together, but those who ran out were killed by the high walls they had built along the village streets falling on them. Dr. Griffiths . . . says that what the Khasias [the indigenous peoples who inhabited the Khasia Hills of the Shillong Plateau (La Touche 1883)] feel most is that the stone boxes in which the ashes of the dead are kept have been shaken to pieces. They consider it a great disgrace that the ashes should be exposed to view. The cemetery (English) here is in a woeful state. Most of the tombs have fallen over and sunk down into the ground, which has all become a loose sand.

La Touche descended the southern edge of the Shillong plateau in heavy rain just before the 2 August M = 6 aftershock (Ambraseys and Bilham 2003), but it is not known whether his seismoscope recorded it. He visited two more villages (Chhatak and Sonamganj) before catching the steamer from Sylhet to Goalhindo and the train to Calcutta. His photograph of the damaged Inglis monument at Chhatak forms the frontispiece to Oldham’s 1899 memoir. On the paddle steamer he recounted losing, and (fortunately for us) finding, his notes on the earthquake, which he continued to transcribe en route.

La Touche’s letters to Nancy continued and included the following:

Steamship Manipur, 6 August 1897

I have done a good bit of my earthquake report and hope to get it nearly finished by tomorrow, at least all the drawings done. I finished the plans and sketches today, at least all except one or two at Cherrapunji which won’t take long. They cover about 30 sheets of foolscap. I hope Mr. O will be pleased with them.

Calcutta, 9 August 1897

I have been hard at work writing all day long and have really got a whole lot of my earthquake report finished. I wish the plaguey thing was quite done. I have got as far as the Shillong cemetery.

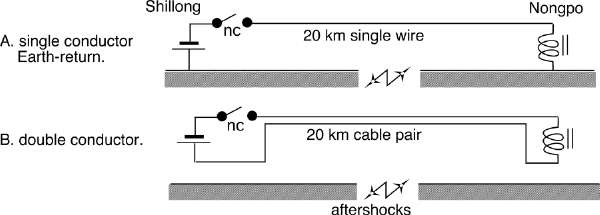

Calcutta, 11 August 1897

The report is finished at last, Hooray! and in Mr. O’s hands. He seemed to appreciate it very much. La Touche’s report appeared as 20 pages in Oldham’s 1899 memoir (appendix A, 257–277). His meticulous observations of thrown and overturned monuments were used by Oldham to calculate local velocities and accelerations. La Touche’s report of deformation of the plateau at Maoflong may have been crucial to Oldham’s decision to request that the geodesists of the Survey of India remeasure the triangulation points on the plateau. Oldham was impressed with two other aspects of La Touche’s report: evidence for electro-telluric potentials associated with aftershocks (figure 10), and La Touche’s inquiries about the telegraph arrival times of aftershocks at Sylhet, Gauhati, and Shillong, which he used to infer their considerable depth (> 10 km).

La Touche describes the activities of the telegraph officers in Shillong in his official report as follows:

Since the first shock occurred the signallers have amused themselves by telegraphing a certain signal [meaning an agreed “alert” code] to Gauhati or Sylhet whenever they happened to be at the instrument and felt a shock, at the same time receiving a signal from either of those places if the shock was felt there. The Telegraph Master assures me that in all cases the shocks are felt absolutely simultaneously at these places. I asked him to note the exact second at which a shock was felt in Shillong, and to ask the signallers at Gauhati and Sylhet to do the same, but he assured me afterwards that no difference could be detected.

He also informed me that an assistant was sent down to Nongpo, on the Gauhati road, as soon as possible after the shock of the 12th June, to restore communication with Gauhati. On attempting to signal through a single wire, with return circuit through the ground, it was found that as each earthquake shock occurred the current was interrupted, or even reversed, when what is called a “closed circuit” was being used, that is, the current was kept continuously flowing through the wire, and interrupted by the key only at the moment of sending a signal. [See figure 10] Apparently the earthquake shocks set up currents in the earth, for, when a second wire was used instead of the earth as a return circuit, no effect of the kind was observed. [Oldham 1899, appendix A, 267–268].

It is not known what happened to the seismoscope records from La Touche’s improved instrument, or why Oldham failed to mention them in his seismometer Appendix E (Oldham 1899, appendix E, 358–359), which describes the selective overthrow of the set of Mallet-designed vertical cylinders at Shillong both in the mainshock and aftershocks. It is possible that Oldham was skeptical of the accuracy of La Touche’s seismoscope, suspicious of its amplification factor, or uncertain about the effects of resonance and friction. If this were the case, Oldham must have subsequently changed his opinion, for somewhat surprisingly (three years after Oldham’s 1902 retirement and return to England) we learn in a letter to Nancy that La Touche has dispatched a copy of his seismoscope, duplicated by Oldham himself, to Simla to monitor aftershocks of the Mw 7.8 Kangra 1905 earthquake.

▲ Figure 10. Erratic telegraph communications occurred between Shillong and Nongpo (figure 2) at the time of Shillong plateau aftershocks when using circuit A and not when using circuit B. The switches were normally closed (nc) and opened only to transmit a pulse. Induced earth-potentials during strong aftershocks reduced or reversed the current induced by the battery in the earth-return circuit A, producing unintentional telegraphic signals. The inferred rupture plane of the Oldham fault projects to the surface between Shillong and Nongpo.

Calcutta, 16 May 1905

An interruption came this morning in the shape of a letter from Mr. Holland asking me to see whether I could rig up a seismograph to be set up at Simla to register the earthquakes, and I have been at that all day. I have sent him one that was made by Mr. Oldham on the same principle as the one I set up in Shillong in ‘97, which is still at work, but I am afraid it is too small to be of much use.

La Touche joined Nancy in Simla for the remainder of August 1897. La Touche, like Oldham, never became director of the GSI, but he was appointed acting director for two years prior to retiring 21 October 1910. A retirement poem dedicated to La Touche by geologist K. A. Knight Hallowes appeared in the Calcutta Englishman for that week. La Touche in previous letters to Nancy characterized Hallowes’ writing as pedantic to the point of stupor; La Touche described Hallowes as “a very flabby individual with a terrible conceit of himself and cannot put his ideas into a concise form on paper.” The final four lines of Hallowes’ tribute read:

Leader and friend, great is our loss of thee.

Mayst thou a well-earned rest in England find.

Rest in this recollection of thy mind,

That thou hast widened Science’s boundary.

In his letter to Nancy that day, La Touche remarks that Hallowes was fortunate to have been on leave from Calcutta, or he would have had “a piece of my mind. Did you ever see such stuff !!”

La Touche published more than 50 articles on the geology of India, completing his last article in Cambridge at age 81, a 576-page geographical index of Indian geology. It was published just after his death on 30 March 1938 (La Touche 1938; Middlemiss 1939). ![]()

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank the British Library and the Centre of South Asian Studies, Cambridge University, for permission to publish the handwritten letters transcribed here, and the Director General of the GSI for permission to publish the photograph of La Touche. I am especially indebted to Dr. Sujit Dasgupta, Deputy Director of the GSI, for his kindness during my visits to the GSI archives in Calcutta. I thank Geoffrey King, L’Institut de Physique du Globe, Paris, and the National Science Foundation for their support during this study.

REFERENCES

Ambraseys, N., and R. Bilham (2003). MSK isoseismal intensities evaluated for the 1897 great Assam earthquake. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 93 (2), 655–673.

Bilham, R., and P. England (2001). Plateau pop-up during the great 1897Assam earthquake. Nature 410, 806–809.

Gee, E. (1934). The Dhubri earthquake of 3rd July 1930. Memoirs of the Geological Society of India 65, 12–15.

LaTouche T. H. D. (1883). Note on the Cretaceous coal-measures at Borsora in the Khasia Hills, near Laour in Sylhet. Records of the Geological Survey of India, 16, 164–166.

LaTouche T. H. D. (1889). On the Barisal Guns. Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, 111–112.

LaTouche T. H. D. (1890). On the Sounds known as the ‘Barisal Guns’ occurring in the Gangetic Delta. Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, 40, 800 (abstract).

La Touche, Rev. J. D. (1897). The late earthquake in India. Nature 56, 444–445.

La Touche, T. H. D. (1897). The Calcutta earthquake. Nature 56, 273–274.

La Touche, T. H. D. Papers, (1880–1913). British Library India Office European Manuscripts, Mss Eur C258.

La Touche, T. H. D. (1938). Geographical Index to the Memoirs Volumes I–LIV, Records, I–LXV, of the Geological Survey of India and General Reports of the Director for the Years 1897 to 1903. Calcutta: Geological Survey of India.

Middlemiss, C. S. (1939). Obituary of Thomas Henry Digges La Touche. Quarterly Journal Of the Geological Society of London 94 (3), cxxvii– cxxix.

Milne, J. (1898). Seismology. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. Oldham, R. D. (1880). Note on the Naini Tal landslip (18 September 1880). Records Geological Survey of India 13, 277–282.

Oldham, R. D. (1899). Report on the great earthquake of 12 June 1897. Memoirs of the Geological Society of India 29, 379 pps..

Oldham, T. (1882a). The Cachar earthquake of 10th January, 1869, by the late Thomas Oldham edited by R. D. Oldham. Memoirs of the Geological Society of India 19, 1–98.

Oldham, T. (1882b). A catalogue of Indian earthquakes from the earliest time to the end of A.D. 1869, by the late Thomas Oldham edited by R. D. Oldham. Memoirs of the Geological Society of India 19, 163–215.

Sweet, M. (1897). Letter to her sister Mrs. Godfrey, 28 June 1897. Small collections, Box 22, Centre of South Asian Studies, Cambridge University. Given by the Reverend J. P. M. Sweet, grandson of May Sweet. Shillong, Assam: 1897.

University of Colorado at Boulder

Department of Geological Sciences

Campus Box 399

Boulder, Colorado 80309-0399 USA

roger.bilham [ at] colorado [dot] edu

[Back]

Posted: 02 May 2008