| Publications: SRL: Opinion |

March/April 2010

Welcome to Portland—Sitting on the Big One

Welcome Seismological Society of America meeting attendees to Portland, Oregon, my hometown! Home of clear blue skies (when it’s not raining), the beautiful Willamette (Wil-LAMette) and Columbia rivers, creeks and lakes galore, majestic volcanic peaks (look to the north and east if it’s a clear day), green trees, trees, and more trees, delicious pinot noirs, and of course, gigantic earthquakes. Not just big earthquakes but gigantic earthquakes, like magnitude (M) 9! Trouble is, hardly anyone knows about it. Well, that’s not exactly true. A good number of Portlanders, Oregonians, and Pacific Northwesterners know that earthquakes can occur in this corner of the country, but unfortunately the majority of people rarely think about these lurking hazards and certainly have not prepared for them.

The biggest and baddest earthquake sits on the doorstep of the Pacific Northwest, or more specifically beneath our beautiful coastline along the Cascadia subduction zone megathrust between the overlying North America plate and the down-going Juan de Fuca plate.

The biggest and baddest earthquake sits on the doorstep of the Pacific Northwest, or more specifically beneath our beautiful coastline along the Cascadia subduction zone megathrust between the overlying North America plate and the down-going Juan de Fuca plate. Yet thousands of high-risk buildings such as unreinforced masonry (URM), tilt-up, preseismic code steel-frame, and vulnerable transportation structures still stand, ready to be damaged or to collapse when the next giant megathrust earthquake strikes. It’s been more than three centuries since the last M 9 shook the Pacific Northwest in 1700. The event generated a tsunami that swept over the beaches of northern California, Oregon, Washington, southern British Colombia, and even Japan. A repeat of such an event could result in thousands of deaths, particularly along the coastline, with significant damage to infrastructure as far inland as the Willamette Valley in Oregon, Puget Sound in Washington, and Vancouver in British Columbia. It could very well be the most catastrophic natural disaster to ever strike the United States.

EARTHQUAKES IN OREGON?

Given this potential scenario, why so much complacency? There are the usual reasons that plague all earthquake-prone areas: denial, competing needs, economic challenges, etc. However, it certainly does not help the cause that almost no one in the Pacific Northwest outside of Puget Sound has ever experienced a big or even moderate-size earthquake. Nothing like being in a big earthquake to provide motivation to be prepared! Strangely enough, despite sitting atop the Cascadia subduction zone, Oregon has experienced very few earthquakes of M 5 in the past 150 years of recorded history and only two, possibly three, events have reached M 6: in 1936 in the eastern part of the state near the town of Umatilla, and in 1993 in the southern part of the state near Klamath Falls, where the state’s first official fatality due to an Oregon earthquake occurred. (Four deaths in Oregon resulted from the 1964 M 9.2 Alaska tsunami.) To the south in 1873, a large M 7.3 earthquake occurred near the Oregon- California border, probably associated with the seismically active Gorda plate. Perhaps the Oregon’s most memorable earthquake was the 1993 Scotts Mill M 5.6 event, which damaged the state capitol. The capitol was retrofitted due to a shaken legislature.

To the north, in the Puget Sound region, large deep earthquakes of M 6.6 to 6.8 have rattled the local residents in 1949, 1965, and most recently in 2001. Outside of Puget Sound, Washington has experienced only one large event, the notorious 1882 M 6.8 North Cascades earthquake.

A FEW WORDS ABOUT THE BIG ONE

Another possible contributing factor to the complacency is the fact that a seismogenic Cascadia subduction zone has been recognized only over the past two decades. Before the mid-1980s, it was believed that the megathrust was aseismic due principally to an absence of observed seismicity.

In 1984, Tom Heaton and Hiroo Kanamori at CalTech became the first scientists to make a persuasive case that the Cascadia subduction zone could rupture in giant earthquakes. In 1987, Brian Atwater of the U.S. Geological Survey, followed by other geologists, worked along the coastal marshes of Washington and Oregon examining buried soils of former forests, marshes that coseismically subsided into estuaries, and tsunami sands. This resulted in the first direct and convincing geologic evidence for such megathrust events. In 1996, Kenji Satake, then at the University of Michigan, uncovered the fact that a tsunami hit the east coast of Japan on 27 January 1700, which more than likely resulted from a large M 9 Cascadia subduction zone earthquake. That really was the clincher.

It is now accepted that numerous giant earthquakes have ruptured along the Cascadia subduction zone megathrust, so efforts now have focused on characterizing the rupture process and recurrence of these giant earthquakes so that future events and their potential hazards can be predicted. For the past decade and a half, Roy Hyndmann and Kelin Wang at the Pacific Geoscience Center (PGC) have been using geodetic and thermal data to define the rupture plane of the megathrust given the inability to image it with seismicity. Obviously, the eastern onshore extent of the megathrust will have a significant impact on ground shaking. The discovery of ETS (episodic tremor and slip) events by Herb Dragert and his coworkers at PGC and understanding the association with the subduction zone process shows immense promise in helping to solve this puzzle.

The intervals between the giant events range from less than 200 years to more than 800 years, with a mean interval of about 500 years. Three hundred and ten years have passed and the time bomb is ticking. Earthquake hazard mitigation doesn’t happen overnight, so we have no time to waste.

Possibly one of the biggest breakthroughs in terms of being able to forecast the next M 9 has been the pioneering work of Chris Goldfinger of Oregon State University and his coworkers, who have collected, examined, and analyzed turbidite (submarine canyon landslide deposits) cores. Chris has been able to identify 19 or 20 events in the Holocene turbidite record that appear to be full-rupture M 9 events, making this record one of the longest and most complete paleoseismic chronologies anywhere. The intervals between the giant events range from less than 200 years to more than 800 years, with a mean interval of about 500 years. Three hundred and ten years have passed and the time bomb is ticking. Earthquake hazard mitigation doesn’t happen overnight, so we have no time to waste.

WHEN THE BIG ONE HAPPENS

In its 2005 publication “Cascadia Subduction Zone Earthquakes: A Magnitude 9.0 Earthquake Scenario,” the Cascadia Region Earthquake Workgroup (CREW) stated in cautious terms that such a future event would result in “unprecedented damage and potentially thousands of casualties.” The effects of the earthquake will be widespread because of the very long rupture area of the megathrust. Along the coast, communities will be subjected to the strongest ground shaking, landslides, and tsunamis. Buildings, roads, bridges, and utility lines will suffer varying degrees of damage with some destroyed. Extensive fatalities and injuries are likely. Within minutes, a devastating tsunami will arrive that will not only impact the Pacific Northwest but other circum-Pacific locations. Coastal communities will be isolated because of landslide damage to roads and runways, and ports and rail lines will be destroyed. In the interior, along the Interstate 5/Highway 99 corridor, tall buildings built before modern seismic provisions were inserted into the building code could be severely damaged with some collapsing in the several minutes of strong shaking, resulting in significant loss of life. Bridges, utilities, and transportation lines will be disrupted, perhaps for months.

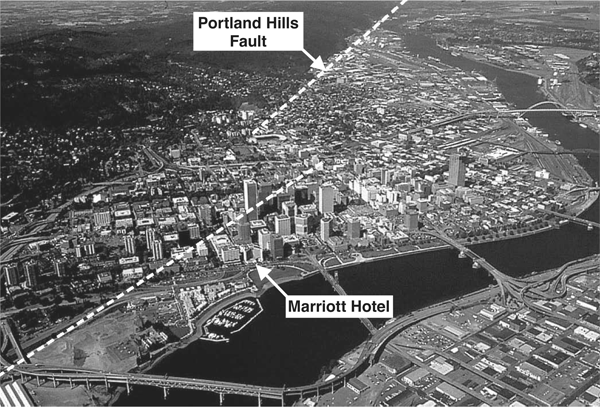

In addition to the Big One, there certainly is also a hazard, albeit poorly quantified, posed by crustal faults and their resulting earthquakes, although you wouldn’t know it based on the historical record. As in past SSA meetings, the Portland meeting is being convened at a location close to an active fault; in this case, two city blocks west of the Marriott Hotel is the poorly studied and certainly poorly understood Portland Hills fault (see Figure 1), a buried west-dipping reverse(?) fault that probably produced the Portland Hills you will see to the west from your hotel room window. Where else would a seismologist want to be?

▲ Figure 1. Aerial view of downtown Portland, showing the location of the Marriott—site of the 2010 SSA Annual Meeting—and the Portland Hills fault. The trace of the fault is based on an analysis of aeromagnetic data by Rick Blakely, USGS. There appears to be a stepover in the fault in downtown Portland. Where else would a seismologist want to be? Photo courtesy of Northern Light Studio.

WHAT TO DO NEXT?

Given the public’s complacency, denial, or lack of awareness of the seismic dangers that lie beneath its feet, it’s little surprise that it’s hard to convince government officials to make decisions on behalf of earthquake safety and even harder to motivate the general public to do, well, anything. If not for a few proactive individuals and agencies such as the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries, better known as DOGAMI, and its hard-charging earthquake safety advocate Yumei Wang, Oregon might still be in the same state of readiness as Kansas. Washington is probably a little better off in preparedness because of fairly regular reminders such as the 2001 M 6.8 Nisqually earthquake and advocates such as Craig Weaver of the USGS and the organization CREW.

So what needs to be done to get to a state of readiness? CREW recommends:

- Reducing the risk for public facilities such as hospitals, schools, police, and fire through upgrades. Funding and possibly legislation will be required to undertake such efforts.

- Retrofitting high-risk buildings such as URM, tilt-up structures, and tall buildings not built to modern codes. A disproportionate number of schools and some other essential facilities are URM.

- Protecting transportation infrastructure such as roads, bridges, airports, water ports, and railroads. These structures will be badly needed in the aftermath of a great earthquake.

- Continuing public education efforts about earthquake dangers and encouraging individual preparedness.

These are great goals; however, they are generic. What specifically needs to happen? First of all, we need to recognize that a sustained effort over years, if not decades, will be required to make the necessary changes. In my humble opinion, a good start would be for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to become more proactive in the Pacific Northwest, with a greater focus on earthquake issues. (More people would die in a tsunami following a great earthquake than likely will die in a terrorist attack.) I’d like to see a Pacific Northwest version of the successful earthquake preparedness handbook Putting Down Roots in Earthquake Country. A significant problem is the lack of champions in the Pacific Northwest, particularly in Oregon. We have a few committed individuals, as mentioned above, but it’s going to take more than a few to do the job. The bottom line is that progress in earthquake hazard mitigation can only be achieved through better understanding and improved communication among members of the scientific, engineering, emergency management, and policy communities. This will result in a “new community” dedicated to seismic risk reduction.

More individuals have to step up to the plate, especially scientists and engineers. We understand the problem better than anyone else. If you’re a scientist or engineer, have you thought about the building you work in? If you are also a parent, have you thought about the condition of your child’s school?

More individuals have to step up to the plate, especially scientists and engineers. We understand the problem better than anyone else. If you’re a scientist or engineer, have you thought about the building you work in? If you are also a parent, have you thought about the condition of your child’s school? Many Oregon schools may be collapse hazards in the event of an M 9 earthquake. Find out, and if the school is a potential hazard, tell other parents, the PTA, the school administration, whoever, and take action!

It’s not easy for individuals to make an impact, but groups of individuals certainly can. Scientists, engineers, and other professionals interested in earthquake safety can make their voices heard when they band together in professional organizations. The Earthquake Engineering Research Institute has been an effective organization in hazard mitigation, and I would like to see a local chapter formed in Oregon to work at the grassroots level. Other organizations such as the Structural Engineers Association of Oregon, the American Society of Civil Engineers, the Association of Engineering Geologists, and the National Emergency Management Association, to name a few, need to join the battle. I’d like to say SSA should join in, but there are too few members in Oregon and fewer interested in earthquake safety. SSA has historically been focused solely on research, although efforts have been underway the past decade to become involved in earthquake safety-related issues. I credit past President Robin McGuire for motivating this change.

To this end, SSA is sponsoring a public Town Hall Meeting during its annual meeting on Wednesday, 21 April 2010, at 6:30 p.m. in the Marriott Hotel.

To this end, SSA is sponsoring a public Town Hall Meeting during its annual meeting on Wednesday, 21 April 2010, at 6:30 p.m. in the Marriott Hotel. We will bring together a group of prominent earthquake experts, emergency managers, and public officials to present to the public the latest information in a presentation called “The Big One Is Coming: What Are You Going to Do About It?” Speakers include Sam Adams, mayor of Portland; Peter Courtney, Oregon State Senate president; George Priest and Yumei Wang of DOGAMI; Jed Sampson and Carmen Merlo, City of Portland; Craig Weaver, USGS; and myself, coordinator of the meeting. We welcome you to attend the Town Hall Meeting and join us in this effort to educate, re-educate, and motivate the people of the Pacific Northwest to prepare for the next big earthquake. See you in Portland! ![]()

P.S. As this article goes to press, the Haiti earthquake has just occurred. The images of suffering are hard to take. In this horrendous event, a young lady named Molly Hightower, who recently graduated from the University of Portland, died when the hotel she was in collapsed. Molly was in Haiti working with orphans. My heartfelt sympathy goes to her family and friends for the loss of this selfless person and to all those who suffered in this catastrophe. I can only imagine what an unspeakable loss this is. The scale of loss in the Pacific Northwest in a big earthquake will never approach that of the losses in Haiti, but it is my wish, no matter how unrealistic it may be, that no family wherever they may be ever suffer such a loss in an earthquake. I ask that scientists, engineers, and others become involved in earthquake hazard mitigation and make a difference like Molly Hightower made a difference.

To send a letter to the editor regarding this opinion or to write your own

opinion, you may contact the SRL editor by sending e-mail to

<lastiz [at] ucsd [dot] edu>.

[Back]

Posted: 04 March 2010