5 February 2026—The magnitude 6.9 earthquake that took place in 2018 on the south flank of Kīlauea on the Island of Hawaiʻi may have stalled episodes of periodic slow slip along a major fault underlying the volcano, according to a new study by scientists at the U.S. Geological Survey.

Since the rupture, slow slip events have stopped on this portion of the fault, and it may take almost 60 years to rebuild the amount of stress that was released during the earthquake on these slow-slip patches, the researchers report in the Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

The researchers also observed no signs of viscoelastic relaxation—a flow of the lower crust and upper mantle in response to stress changes—after the earthquake.

These features of the 2018 earthquake can be useful for understanding and evaluating earthquake hazards on this part of Kīlauea, said Ingrid Johanson at the USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory and colleagues.

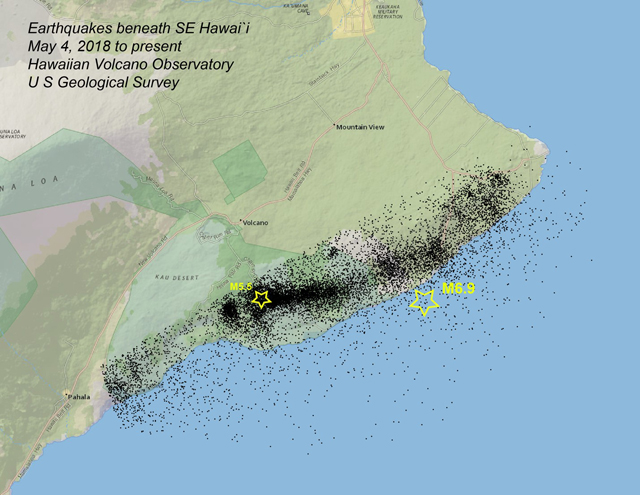

The May 4, 2018 earthquake occurred in the middle of a massive eruption of the volcano’s East Rift Zone. The earthquake ruptured part of Kīlauea’s décollement fault, where the volcanic pile meets the underlying oceanic crust.

The region is densely instrumented with Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) stations, which measure changes in land levels to create an overall picture of how the Earth’s crust moves and deforms before, during and after earthquakes and eruptions.

Johanson and colleagues used these data to look at where fault slip took place during and after the earthquake, to compare with areas of slip from past earthquakes and past slow-slip events. Compared to the sudden rupture of an earthquake, slow slip seismic events can release energy over weeks and months.

The 2018 earthquake ruptured through patches of the fault where slow slip events have occurred somewhat regularly over the past two decades. But these events have not been observed since the 2018 earthquake.

The researchers calculate that the earthquake may have released almost 60 years’ worth of stress built up along the fault in these patches, and that the resulting “stress shadow” may keep these events from happening again for decades.

“Assuming steady loading from fault creep, we calculate that [the slow slip fault regions] could be in stress shadow for 56 years, plus or minus 3 years,” said Johanson.

“However, loading on the décollement fault is strongly connected to volcanic activity, so a change in volcanic activity could push the fault out of the stress shadow early and we shouldn’t rule out the possibility of a through-going rupture in the same location within the projected 56 years,” she added.

One of the events that the researchers were hoping to study during the 2018 event was postseismic viscoelastic relaxation, which offers a unique chance to observe crust and mantle deformation, the researchers noted.

“So although the 2018 earthquake occurred within the first week of an historic eruption and caldera collapse and one day after lava first erupted from a fissure in Leilani Estates,” Johanson said, “it was a priority to capture the deformation pattern following the earthquake and to make sure that additional portions of the flank were instrumented.”

However, Johanson and colleagues found minimal afterslip on the fault and no signs of viscoelastic deformation.

The researchers say it’s possible that the dip of the décollement fault is so shallow that it remains within the brittle upper portion of the crust and might not transfer stress into the lower crust and upper mantle to cause deformation.

“Given its rupture area, it is likely that the 1975 magnitude 7.7 Kalapana earthquake also remained in the brittle portion of the crust, as may future events in this size category,” said Johanson. “However, it is hypothesized that the 1868 magnitude 7.9 Great Kaʻū earthquake ruptured the décollement all the way below Mauna Loa. If another rupture occurred to this depth, then it might put enough stress into the lower crust to generate a [viscoelastic] response.”

The 2018 earthquake originated on the same part of the fault as the 1975 Kalapana and other historic Kīlauea south flank earthquakes. It’s possible that magma intrusion through this part of the fault was responsible for these earlier earthquakes, as appears to be the case for the 2018 earthquake.

“This emphasizes that monitoring volcanic activity is key for understanding stress accumulation and earthquake activity on Kīlauea’s south flank and highlights how connected magmatic and tectonic processes are in Hawaiʻi,” said Johanson.