16 June 2025—If plate tectonics are canon in the Earth sciences, the details of what makes up a “plate” are surprisingly tricky, says Hannah Mark.

“The definition of a plate is a section of the outermost solid layer of the Earth that behaves as a rigid body, and deforms only at its boundaries,” she explains. “But anything past that first order, it all breaks down in interesting ways. And that’s kind of where all the good science happens, right?”

Mark, a geophysicist and Lamont Assistant Research Professor at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, studies past that first order of plate tectonics, looking at mantle dynamics, the structure of the lithosphere and the processes taking place at the boundary between the two.

“There are things it seems like we should know about tectonics, but are still working on,” she says. “For instance, can you seismically image a fault that goes all the way through the crust into the mantle? Is it possible to have a fault there, and how would we know if we were seeing it or not?”

She went to the University of Chicago thinking she might be a physicist and study the universe. But “as one of the last classes at my university that got a paper catalog, in the dorm we would flip through it and see what the weirdest course we could find was,” Mark recalls. “And that’s how I discovered that we had a department of geophysical sciences.”

In a tectonics course taught by the late David Rowley, the class read Alfred Wegener’s classic, The Origins of Continents and Oceans. For Mark, it showed that “you can study these things that happen really slowly on very long time scales, and they have a certain power to them,” she says. “It just kind of got into my head.”

Mark uses seismic data to image the Earth’s subsurface and learn more about how this region relates to mantle dynamics. Some of the data she works with are passive data collected by seismic stations around the world, but she also participates in fieldwork that collects active source seismic data.

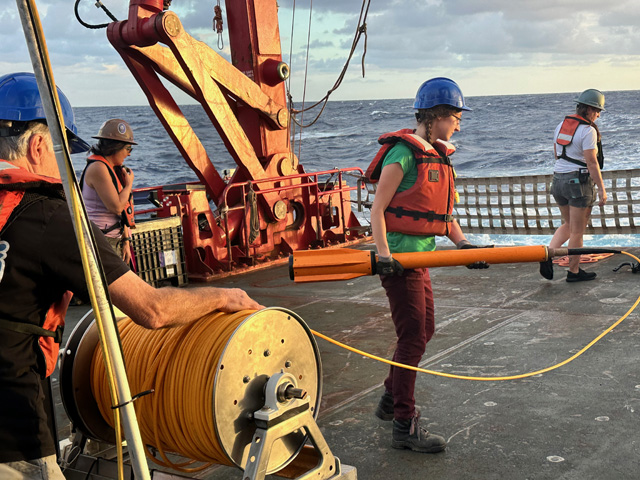

Last January, she was part of a scientific expedition cruise to the western Pacific Ocean that collected both seismic and magnetic data from the seafloor, using hydrophones to pick up seismic signals created by airgun blasts in the water column. The magnetometer—which looks “sort of like a big orange torpedo towed on a cable behind the ship,” she explains—gathered information on ancient changes in the direction of the Earth’s magnetic field recorded by minerals in the oceanic crust.

New crust is created at ocean ridge spreading centers. As the new crust moves away from the spreading center, the magnetic signatures it bears represent a sort of history of the formation of the ocean basin and what the Earth’s magnetic field was doing when that crust was formed. The seafloor at Mark’s study site “is among the oldest seafloor that’s still on the Earth’s surface,” she says, “a Jurassic-age seafloor from when the Pacific first started opening.”

Researchers think there were three spreading ridges in this proto-Pacific, “branching out around a little triangle of the early Pacific plate, so it gave us three seafloor records of the same time period,” says Mark.

Two of those magnetic records have already been surveyed, “and given some contradictory results as to what the magnetic field was doing,” she explains, “so we went to survey the third set of magnetic records.”

Mark is also still working on active seismic source data collected from an earlier cruise in the central Aleutian Islands, looking at how volcanoes in subduction zones form new crust.

While she was finishing her Ph.D. at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Mark participated in a seminar that paired scientists with journalists to build the researchers’ public communication skills. Mark has written about her work for several outlets.

“Some of the stuff I work on does feel esoteric at times, but I think there’s a lot of value in putting that out into the world, because I think there are a lot of people who don’t identify as scientists or even science-curious but have a lot more innate curiosity than we might give them credit for,” she says.

Her own grandmother “loves to hear about whatever her grandkids are doing, including asking me detailed questions about plate tectonics whenever I see her, so she’s kind of my audience ideal,” Mark says.

SSA At Work is a monthly column that follows the careers of SSA members. For the full list of issues, head to our At Work page.