The generosity of Clarence Allen (1925-2021), SSA’s 41st president, will bring career-changing opportunities to countless scientists in our community.

The Seismological Society of America (SSA) announced today that it has received a gift of nearly $1.6 million, a bequest from the estate of renowned seismologist Clarence Allen. The gift from the Caltech professor emeritus of geology and geophysics is the largest donation in the Society’s 115-year history.

“Clarence was known for his generous spirit,” says SSA President John Townend. “He volunteered his time and talents to our community, as our leader, as a guide to newcomers in seismology and as an advocate for policy changes that have made our world a safer place. His final gift to our Society has left us overwhelmed with gratitude. This donation will transform SSA.”

Allen was 96 when he died on 21 January 2021. Throughout his distinguished career, his dual expertise in seismology and geology served him well in his research, in his advocacy for effective hazard mitigation, and in his many leadership roles across the scientific community. Those roles included service as president of both SSA (1975) and the Geological Society of America (1974).

Allen’s wisdom still speaks from his thesis, which shed light on the structure of the San Gorgonio Pass area of the San Andreas Fault (“a remarkable piece of work everyone appreciates,” says Hiroo Kanamori, John E. and Hazel S. Smits Professor Emeritus of Geophysics at Caltech). It still speaks from the pages of many a well-worn copy of “The Geology of Earthquakes,” (Oxford University Press, 1997), the book Allen co-authored with Robert Yeats and Kerry Sieh. And it speaks from his many influential papers such as 1974’s “Geological Criteria for Evaluating Seismicity,” in which he argued that the geologic record “is a far more valuable tool in estimating seismicity and associated seismic hazard than has generally been appreciated.”

Allen’s friends and former colleagues describe him as a gifted scientist and communicator. “I think that his greatest scientific accomplishment was in clarifying and advancing knowledge of the relation between seismicity and faulting,” says Paul C. Jennings, Caltech professor emeritus of civil engineering and applied mechanics. “Because of his knowledge and gentle manner, he also was a very good member and often, chair, of many scientific committees.”

Terry Wallace, director emeritus of the Los Alamos National Laboratory and past president of SSA, earned his doctorate at Caltech and recalls how Allen always steered the conversation at the university’s Seismological Laboratory coffees so that every scientist could participate. He still marvels at Allen’s “incredibly evenhanded” evaluations of every single forecast that came to him as chair of the National Earthquake Prediction Council (1979-84). And no matter where he led students on field trips, Allen’s geological insight made the journey “magical,” Wallace says. “He could make the rocks talk and tell a story.”

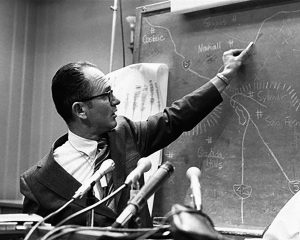

In the aftermath of the devastating 1971 San Fernando Valley Earthquake, Allen began making the rocks talk to policymakers. He used his experience in the field and what Wallace describes as “his clear, articulate voice” to tell legislators “you have to pay attention to geology. Geology could have told you this earthquake would happen where it did.” Allen chaired the National Academy of Sciences Committee that examined the initial scientific and engineering lessons of the event and published its findings in 1971. The following year, the Alquist-Priolo Earthquake Fault Zoning Act was signed into law in California, prohibiting building across active faults.

Allen is also remembered for his contributions to the 1970 Report of the Task Force on Earthquake Hazard Reduction, published by the Office of Science and Technology Policy, and his work lobbying for the formation of the National Earthquake Hazards Reduction Program. “No one should underestimate his role in getting that first act passed [in 1977],” Wallace says. “He used his position at SSA as a bully pulpit for the public good.”

Jennings recalls how Allen could “assess geological and seismological data and research from the viewpoint of its relevance to earthquake performance and engineering design,” and points to one illustrative example. Allen’s research that showed that “most, if not all, of the largest reservoir-triggered earthquakes were in areas where there was evidence of geologically recent faulting, a result that showed how to approach this problem.”

Kanamori also counts Allen’s work in hazard mitigation among his greatest contributions, contributions that many people may not appreciate, he says, because “Clarence was a very modest person.”

Colleagues note that Allen wasn’t one to publicize his contributions himself, but they were recognized with numerous awards and honors, from Allen’s G. K. Gilbert Award from the Carnegie Institute of Washington, D.C. in 1960 to his George Housner Medal from the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute in 2001. He was elected as a fellow to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1974 before his election in 1976 to both the National Academy of Engineering and the National Academy of Sciences. The California Earthquake Safety Foundation awarded him the Alfred E. Alquist Award for public service in 1994.

In 1996, Allen received the Medal of the Seismological Society of America for his contributions to seismology and earthquake science. At the awards ceremony he reflected on his childhood in a “family of inveterate travelers and campers,” recalling the time his father piled the Allens into a 1927 Dodge to travel from their home in Southern California, to Eugene, Oregon, “without ever getting on a paved highway.”

Allen said that his family’s early expeditions, and later, during World War II, his volunteer service in the U.S. Army Air Corps, which found him examining maps over the Pacific as a B29 navigator, “were largely responsible for my interest in things geographical that ultimately—and luckily—led me into geology and geophysics.”

Allen’s military service interrupted his undergraduate studies at Reed College but he returned to earn his B.A. in physics in 1949 before heading to Caltech to pursue his master’s degree in geophysics (1951) and his Ph.D. in geology (1954) with the aid of the G.I. Bill.

In a 1994 interview with Caltech, Allen described his migration from geophysics to geology: “It was a matter of what I was interested in. Particularly, I discovered I had this love for field geology, the mapmaking aspect of it, and trying to figure out what the three-dimensional configuration of geologic structures was. At that time, and even today, I hope, there’s no great boundary between the two fields. No one was particularly worried that I had to be one or the other. When it came time to do my thesis, I decided I’d like to do a geologic field problem. And that’s what I did out in San Gorgonio Pass. I wasn’t giving up on geophysics, but I think that by the time I left here I was probably more of a geologist than a geophysicist.”

After a brief teaching stint at the University of Minnesota, Allen returned to his home state to join the Caltech faculty in 1955, and enjoyed the stimulating exchange of ideas with colleagues like Kanamori, Don Anderson, Beno Gutenberg, Frank Press and Charles Richter.

In the 1960s, Allen was known to keep a packed backpack and suitcase inside his office so he was ready to explore any surface fault that called from around the globe. Kanamori recalls one of Allen’s most interesting stories from these research trips. “Hugo Benioff had an idea that the entire Pacific is rotating clockwise and expected to find a right-lateral fault in the Philippines. Clarence was sent there to find out. He went there and found the opposite (left-lateral), and Benioff quickly dropped his idea,” says Kanamori. “I thought that this illustrates very well how scientific research goes. It does not always go forward; very often it goes backward, but after all we make progress. I learned many lessons from Clarence.”

It’s been said that Allen had an impressive skill for 3-D visualization and a photographic memory for faults. But there is one word that comes up again and again when talking with the people who knew him best.

“His kindness,” says Lucile Jones. “That is the first thing that comes to mind about Clarence.” The founder and chief scientist of the Dr. Lucy Jones Center for Science and Society remembers getting to know Allen at the Caltech Seismological Laboratory when she began work at the USGS. At the time, she was the only female with a doctorate in earthquake science at both the university and the agency. “Clarence was the kindest person to me at a place where I was finding my feet. He didn’t care if I was a man or woman. He made me feel comfortable. He didn’t have an ego. He was never competitive.”

Jones recalls how their mutual interests in China and earthquakes sparked many interesting conversations. And she still laughs when she remembers the time they needed to determine the magnitude of an earthquake in the face of an equipment mishap that left their data clipped. “Clarence studied the paper we had just pulled off the drum and said, ‘It looks like a 6. What do you say we call it a 6?’”

“He had this twinkle in his eye,” she says. “He was just a genuinely happy person with an open curious mind. He found joy in his work and the people he knew.”

“Exceptionally gracious and kind” is also how Susan Newman remembers Allen. Newman, the executive director of SSA during Allen’s presidency, describes him as a “highly respected leader” whose “clear observations, quick wit and easy manner brought varied people together — geologists, seismologists and engineers.”

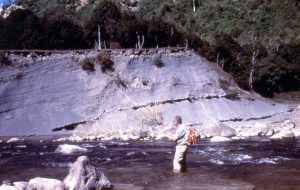

An avid hiker and fly fisherman, Allen once quipped that “my most remarkable discovery has been that big earthquakes and big trout tend to occur in the same parts of the world.”

Allen’s nephew Jim Lefeber was one of many he shared his love of the outdoors with, introducing him to the Eastern Sierra and taking him on many backpacking adventures in search of Golden Trout. It wasn’t the only door he opened for his nephew, who describes his uncle as “an incredibly generous man.” “My family could not afford for me to attend college,” Lefeber said. “Uncle Clarence stepped up and paid for my tuition.”

(Photo by Paul Jennings)

Jennings also accompanied Allen on many a trout fishing trip. “I will miss reminiscing about them and sharing with him results of my recent outings,” he says.

Other SSA members say they will miss talking seismology over coffee with Allen and receiving his emails with questions to ponder about the natural world. But, through his gift, Allen will help spark new questions and ideas for the SSA community to ponder and resolve for many years to come.

Following careful deliberation, the SSA Board of Directors will use Clarence Allen’s gift to create a special fund supporting student and early-career member involvement in scientific conferences, as well as community grants to support programs and events within the SSA community that serve to advance earthquake science, with a special focus on developing seismologists. The fund is planned to be fully realized and operational by 2024.

Learn more about Clarence Allen’s life and career in his own words:

The California Institute of Technology Archives Oral History Project Interview with Clarence Allen

Connections: The EERI Oral History Series Interview with Clarence Allen